Late this summer I attended a workshop at the Penland School of Craft – a scenic community outside of Asheville in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. Founded in 1929, the craft-based school hosts residencies and one-to-three-week workshops. It also offers housing for both its teachers and students.

Over the weekend we visited the river down the road where Nevada and Maggie pulled abaca and cotton fiber sheets.

The whole experience felt incredibly romantic. Each day, I woke up, walked to breakfast, met artists interested in all sorts of craft arts (basket weaving, sand casting, woodworking), hiked around campus as fog cleared, and learned about papermaking from some of the most experienced and enthusiastic teachers I have ever met.

Susan Gosin with an artist book she made in collaboration with a poet.

The course, “Contemporary Papermaking for Book Arts”, was taught by Susan Gosin and Cynthia Nourse Thompson. Gosin, founder and co-chair of Dieu Donné, is a luminary in the papermaking world and continues to work collaboratively with artists to create limited edition books. I particularly enjoyed learning about her projects with William Kentridge. Thompson is an artist, curator, and teacher of paper and book arts. She teaches at KSU and was previously the director of the MFA programs in Book Arts + Printmaking and Studio Arts at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. With her curatorial work, she has gotten to research and meet artists across the country. She always had an artist or two or three for me to look up if I wanted to learn more about a technique or idea.

Beating the fiber

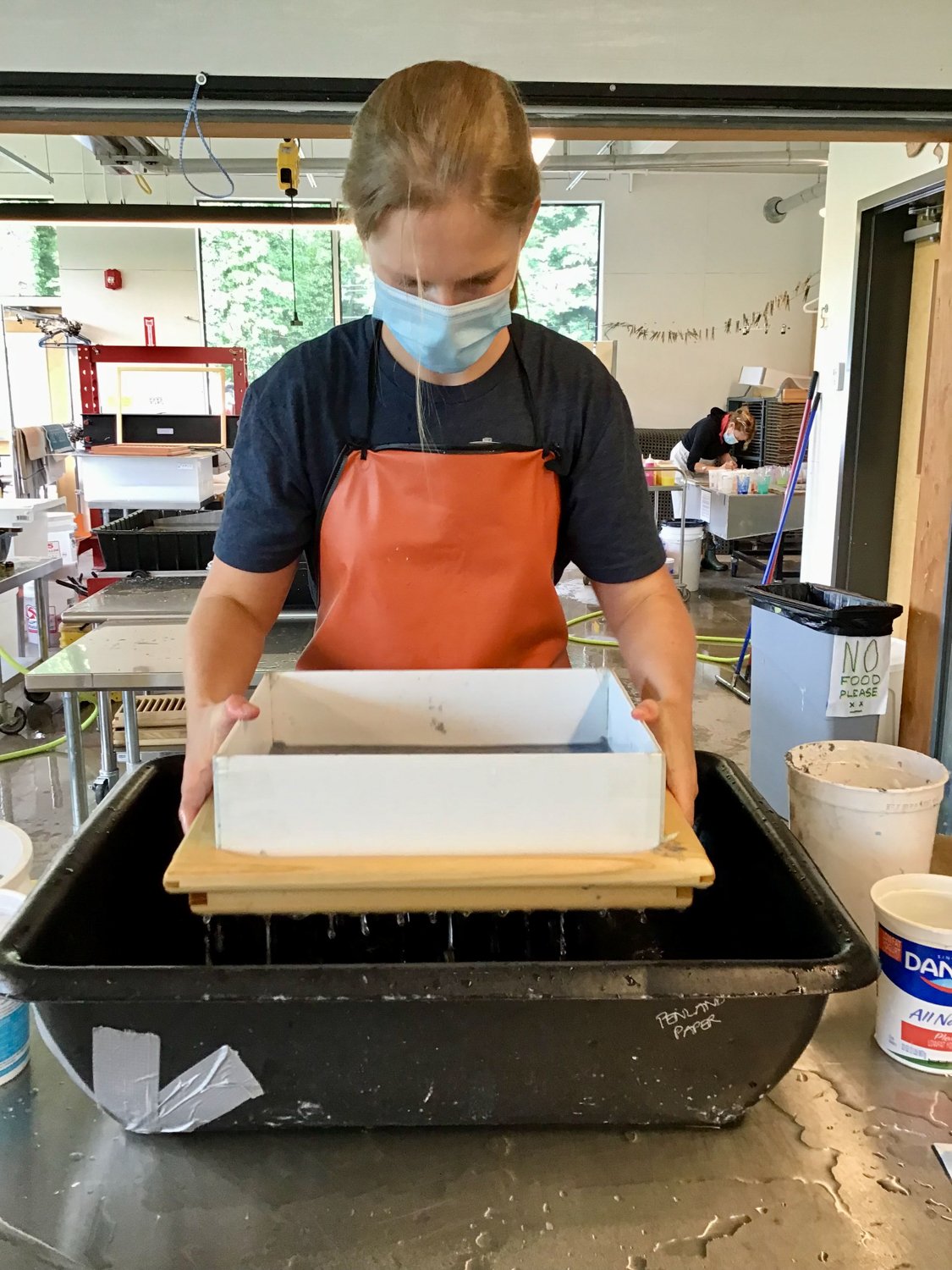

The first week was heavy in instruction. Learning the process of beating (cutting the fiber), pulling (scooping fiber out of a vat of water and pulp), couching (transferring the pulp from the mould to a pad of felts), pressing (to remove excess water), and drying. We primarily worked with cotton, abaca, and linen.

It was a little awkward pulling sheets at first. If I pulled too little fiber from the vat, the fiber wouldn’t come off the mould. If I pulled too much, the fiber would slide around as I couched it.

By the second week, I was fairly comfortable with the process. I began experimenting and using a deckle so that I could mix colors.

Sheets of dried handmade paper with pigmented pulp.

Pulp painting, since the surface is so fragile, is somewhat difficult to control, so stencils are essential. I have always avoided stencils. The process of planning and cutting into mylar can be frustrating and stifling, but pulp painting changed my attitude entirely. I cut stencils to create windows, streets, moons, and trees.

I placed a stencil of Bristlecone pine on the mould to create a watermark.

At Penland, the Bristlecone pine became a motif in my work. I learned about them over the summer while visiting Great Basin National Park. Bristlecone pines are the oldest (non-clonal) living species on the planet. They are gnarly looking, slow-growing, and dense. At 3000-4000 years old, these trees are beautiful beacons for deep time at a human scale.

Pressing the paper (removing excess water) before loading it into the drying system.

Nevada and I celebrated after successfully loading the drying system for the first time.

Putting the paper through the drying system felt similar to processing film or putting a print through the printing press – a combination of time, mystery, and excitement. Over the course of 24 hours, the surface becomes rough or smooth, the paper strong or weak, and the color vibrant or subdued.

Because the workshop was somewhat longer at two weeks and everyone stayed on campus, I got to know my classmates fairly well. Everyone was kind and interesting. And, they came from across the country. I loved spending time with them and observing how they approached art marking.

Maggie’s weaving background inspired her paperwork.

I returned to Houston with a pack of cotton, linen, and abaca sheets for future projects. They are stronger and lighter than my store-bought paper. I love handling them and noticing how each one’s unique oddities. For now I’ll keep them tucked away, but every once in awhile I will treat myself to one of these small treasures.

Drum leaf bound book with a handmade abaca paper cover.